Adolygiad Llyfr: The Gospel According to James Baldwin

Gan Y Parchg Ganon Jarel Robinson-Brown, Pregethwr Ganon yn Eglwys Gadeiriol Deiniol Sant, Bangor.

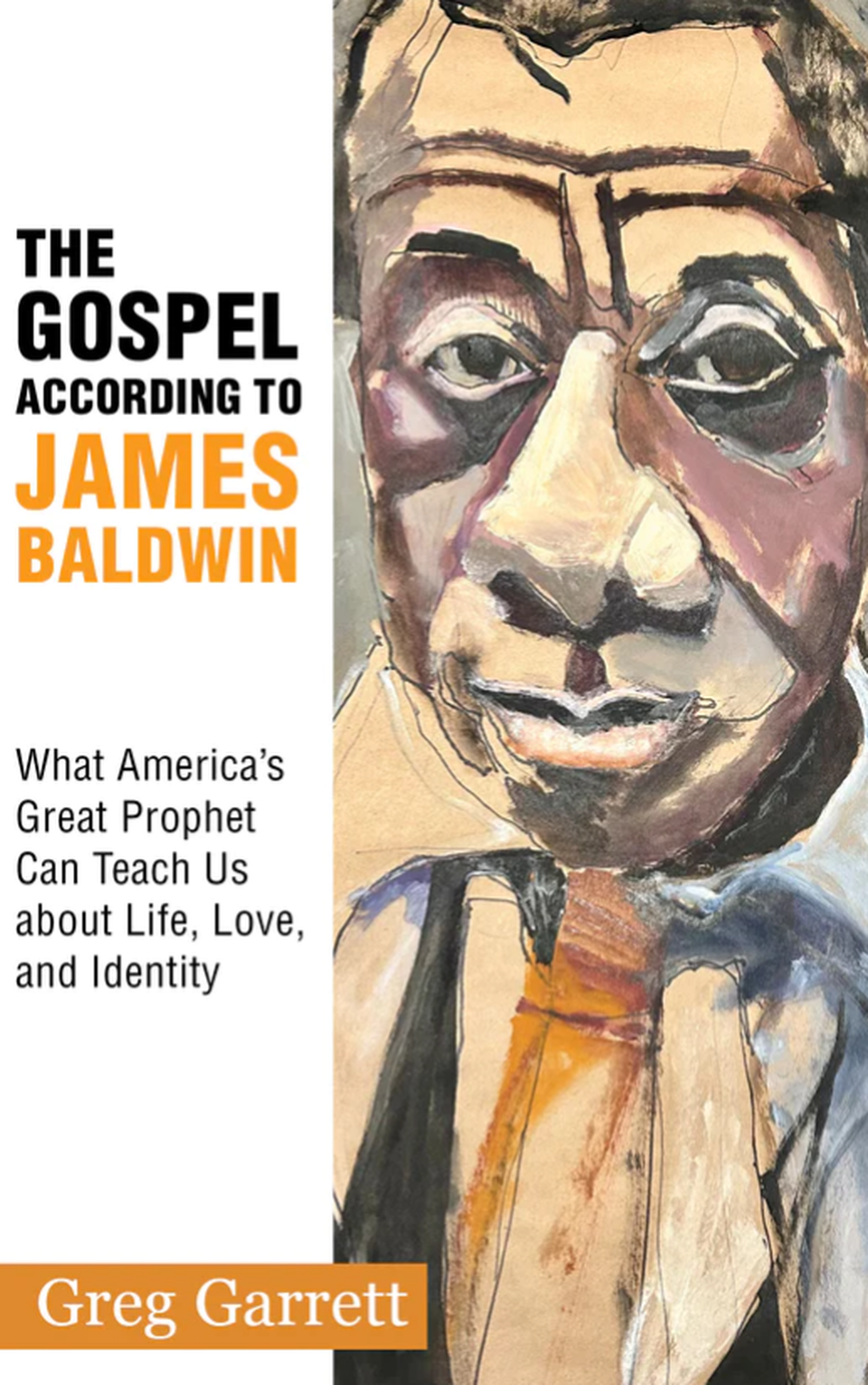

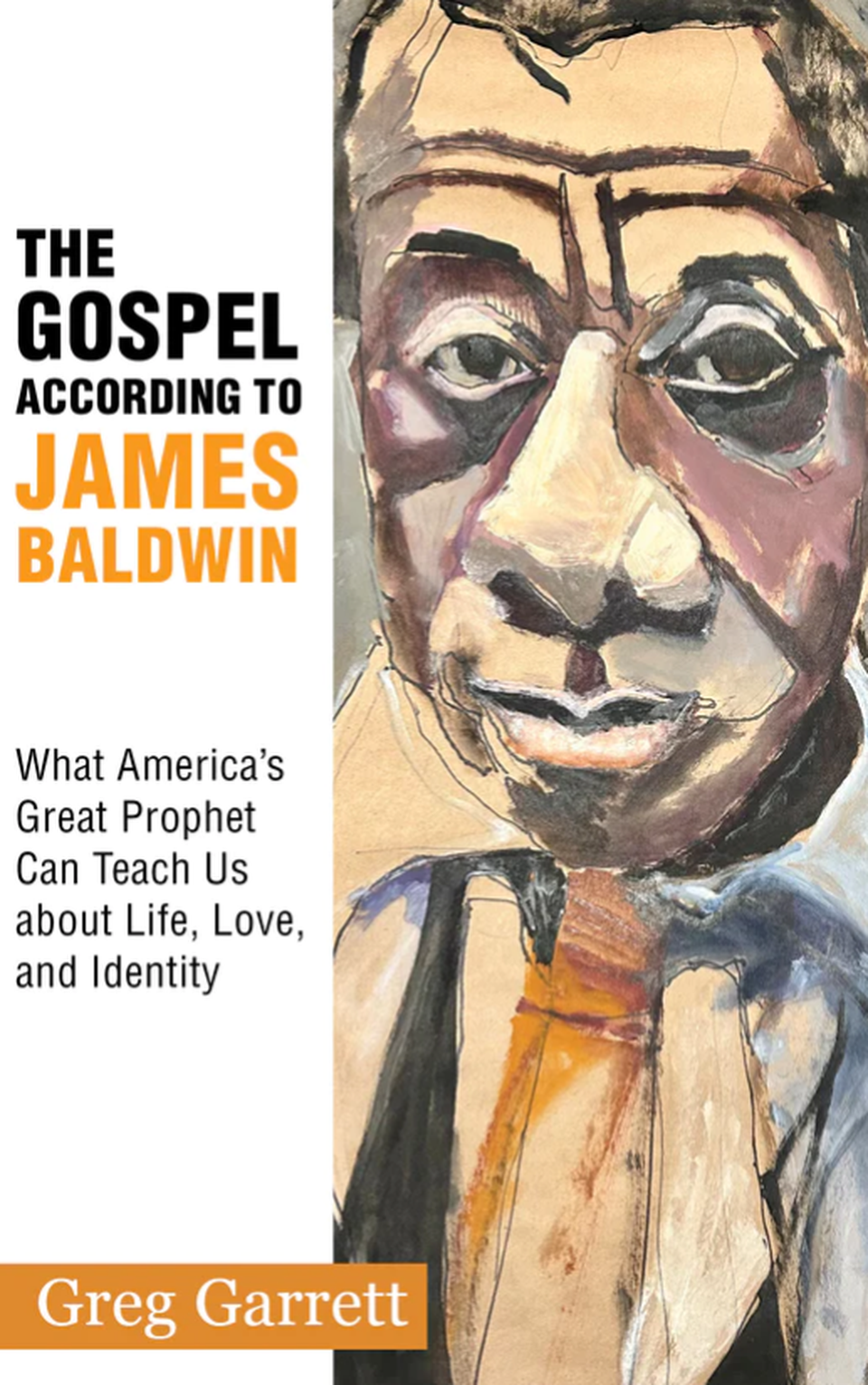

The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America's Great Prophet Can Teach Us about Life, Love, and Identity

Gan Greg Garrett

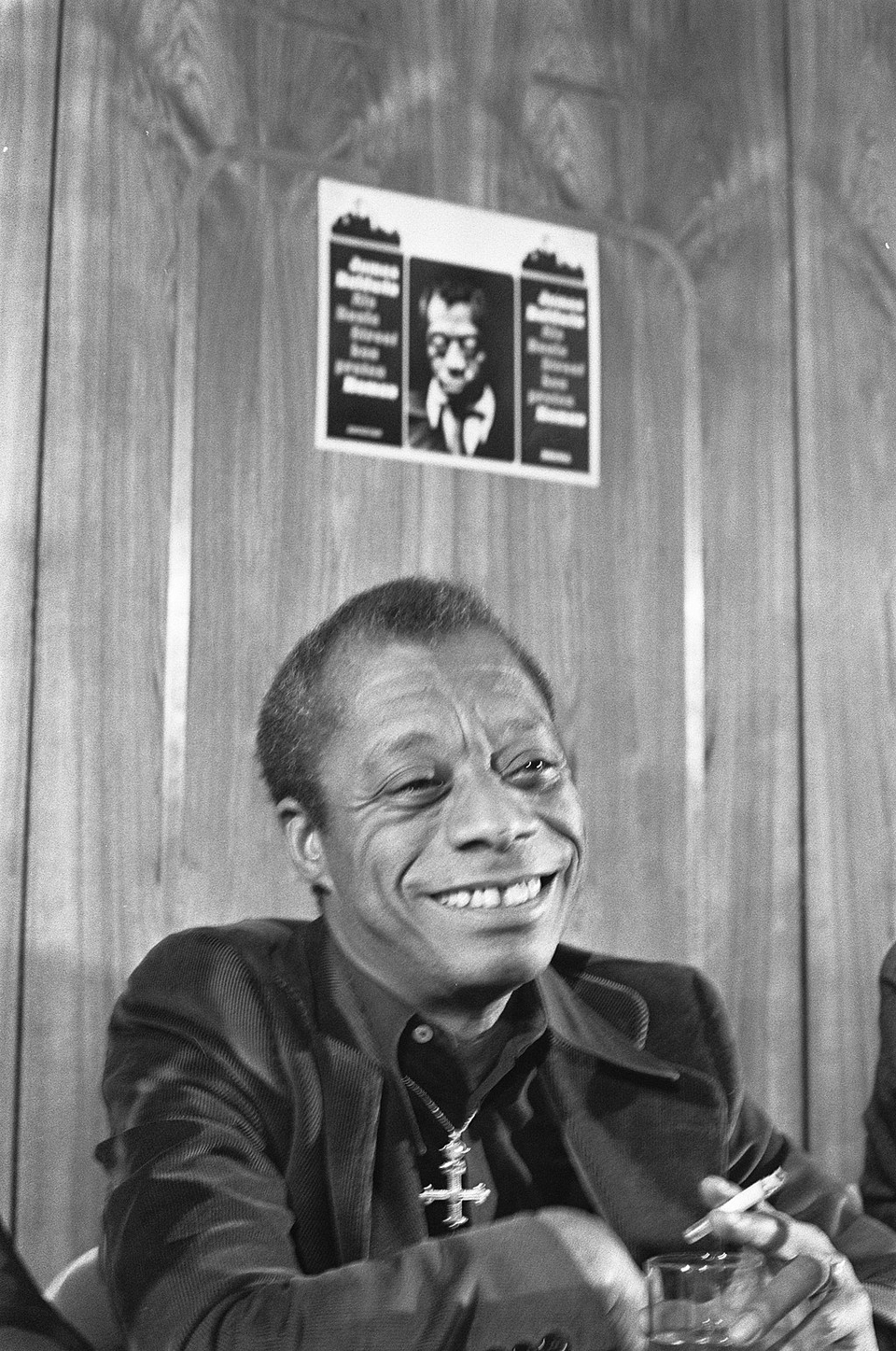

Ganed James Arthur Baldwin ar 2 Awst 1924 yn Ysbyty Harlem, Efrog Newydd. Roedd yn draethodydd, yn ddramodydd, yn actifydd ac yn nofelydd ar adeg pan allai’r gwirionedd yr oedd ganddo i’w gyfleu wedi bod ar draul ei fywyd yn hawdd, ac yn aml, bu bron â gwneud hynny.

Gan ysgrifennu pan oedd y mudiad hawliau sifil ar ei anterth, collodd Baldwin ffrindiau agos yn rheolaidd i drais hiliol a arweiniodd yn rhannol at y penderfyniad i ymgartrefu yn Ffrainc. O’r colledion a ddioddefodd, yn ddiau, y mwyaf arwyddocaol oedd y golled a ddaeth yn sgil llofruddiaeth y Parchedig Dr Martin Luther King Jr, a arweiniodd at ddiffyg ar yr haul dros dro ym mywyd Baldwin.

Rwy’n amau bod Baldwin wedi ystyried King yn ffigwr Tadol, neu o leiaf yn un a oedd yn cynnal gobaith am Gristnogaeth nad oedd wedi colli ei ffordd yn llwyr. Efallai i Baldwin weld yn King rywbeth o’r hyn y mae Garrett yn ei ddisgrifio fel dawn Baldwin ei hun:

‘To be a witness is to tell the truth about the lives we’re living, the lies we’re living. It is to stand up and say what is wrong – and what is right.’ (t.106).

Mae Garrett hefyd yn ein hatgoffa ni fod Baldwin yn ffigwr radical iawn, er gwaethaf ei gyfeillgarwch â King roedd yn cael ei ystyried yn rhy radical i fod ar y llwyfan gyda King ac arweinwyr hawliau sifil eraill, pan wnaeth King ei araith ‘I Have a Dream’. (t.139).

King oedd yr hynaf o naw o blant, yn ŵyr i Affricanes wedi’i chaethiwo ac yn ddyn hoyw agored ar adeg pan oedd cyfunrywiaeth yn dal yn anghyfreithlon, roedd hunaniaeth Baldwin yn golygu ei fod yn gweld pethau ynddo’i hun ac yn y gymdeithas y dewisodd llawer eu hanwybyddu neu gydweithio â nhw’n fwriadol, ac roedd y ffaith iddo ddewis i siarad am y pethau hyn yn dyst i’w ddewrder. I Baldwin, roedd angen i bobl ddu a gwyn nodi’r gwirioneddau am eu hanesion er mwyn bod yn wirioneddol rydd - ond hefyd roedd yn rhaid i’r Eglwys nodi ei hamryw fethiannau a’i rhan ym mhechodau hiliaeth a homoffobia; Eglwys yr oedd Baldwin yn ei hadnabod yn dda iawn fel pregethwr ifanc.

Er iddo adael yr Eglwys, mae cyfrol Garrett yn ein hatgoffa ni o’r ffyrdd y cafodd gramadeg y bywyd Cristnogol ei wreiddio mor ddwfn yn Baldwin fel person, gramadeg sy’n dod i’r wyneb ym mron pob darn o’i waith ysgrifenedig. Dawn fawr Baldwin oedd y ffordd y gwnaeth ef ddweud y gwir wrth y byd am y byd ei hun gan wireddu galwedigaeth sef ‘to bear witness to the truth’ (t.63) ac wrth wneud hynny daliodd ddrych i fyny â’r geiriau: ‘we can be better than we are’ wedi’u hysgrifennu arno i’n hatgoffa ni.

Ar un ystyr rwy’n credu mai dyma ffordd Baldwin o ymgorffori’r Efengyl y daeth i’w hadnabod fel pregethwr ifanc - mae Iesu, yn ei fywyd, ei farwolaeth a’i atgyfodiad - yn rhoi dewis i ni... i droi, at fywyd, at wirionedd, at gariad, ac i gael ein hachub. Ond yn y pen draw, dewis ydyw. Efallai’n fwyaf rhagwybodol i ni fel Esgobaeth yw’r ffordd y mae Garrett yn ein hatgoffa ni o her Baldwin i Gristnogaeth sefydliadol - fel dyn hoyw Du roedd Baldwin yn gyfarwydd ag allgau mewn mwy nag un ystyr.

Ac felly mae’n ein hatgoffa ni yn yr un modd â Garrett, nad yw byth yn rhy hwyr i fod yn bobl y mae Duw wedi ein galw ni i fod. Fel y mae Garrett yn ei ddweud mor hyfryd:

We are all better than our worst acts.

We are always in a state of becoming.

We are each looking for the place we belong and the people who will love and understand us.

And we need the help of writers, artists, priests, and prophets to find those things. (t.25)

Yn ei gyfrol ddiweddar The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us About Life, Love and Identity, mae Greg Garrett yn ein hatgoffa ni o’r cyfoeth diwinyddol ac ysbrydol dwfn sydd ar gael yng ngwaith James Baldwin, agweddau ym mywyd Baldwin, sydd yn fy marn i, wedi cael eu hanwybyddu am gyfnod rhy hir o lawer.

Nid wyf i’n credu bod Baldwin erioed wedi ymweld â Chymru, ond mae’n werth i ni feddwl - petai’n sefyll ym mhulpud Deiniol Sant heddiw - fel y gwnaeth yn Uppsala pan gafodd wahoddiad i annerch Cyngor Eglwysi’r Byd ym 1968 - beth allai fod ganddo i’w ddweud wrthym ni am ein bywyd gyda’n gilydd nad ydym ni eisiau’i glywed, neu nad ydyn ni eto wedi’i gydnabod?

Fel y mae Garrett yn ei ddweud:

If all of us who love and admire Baldwin take [his] calling seriously – to be honest about ourselves and about the world, to call out what is wrong, to stand up for what is right – then we have no choice but to speak, preach, teach, write, march, vote, transport, feed, house, nurture, boycott, and lend our fee and heads and hands to the quest for justice. (t.141)

Mae’r Parchedig Ganon Jarel Robinson-Brown yn Gurad Cynorthwyol yn Esgobaeth Llundain, Ysgolhaig Gwadd yng Ngholeg Sarum, Caersallwg, Cyd-Gadeirydd OneBodyOneFaith a Phregethwr Ganon yn Eglwys Gadeiriol Deiniol Sant, Bangor.

Book Review: The Gospel According to James Baldwin

Book review by The Revd Canon Jarel Robinson-Brown, Canon Preacher of St Deiniol’s Cathedral, Bangor.

The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America's Great Prophet Can Teach Us about Life, Love, and Identity

By Greg Garrett

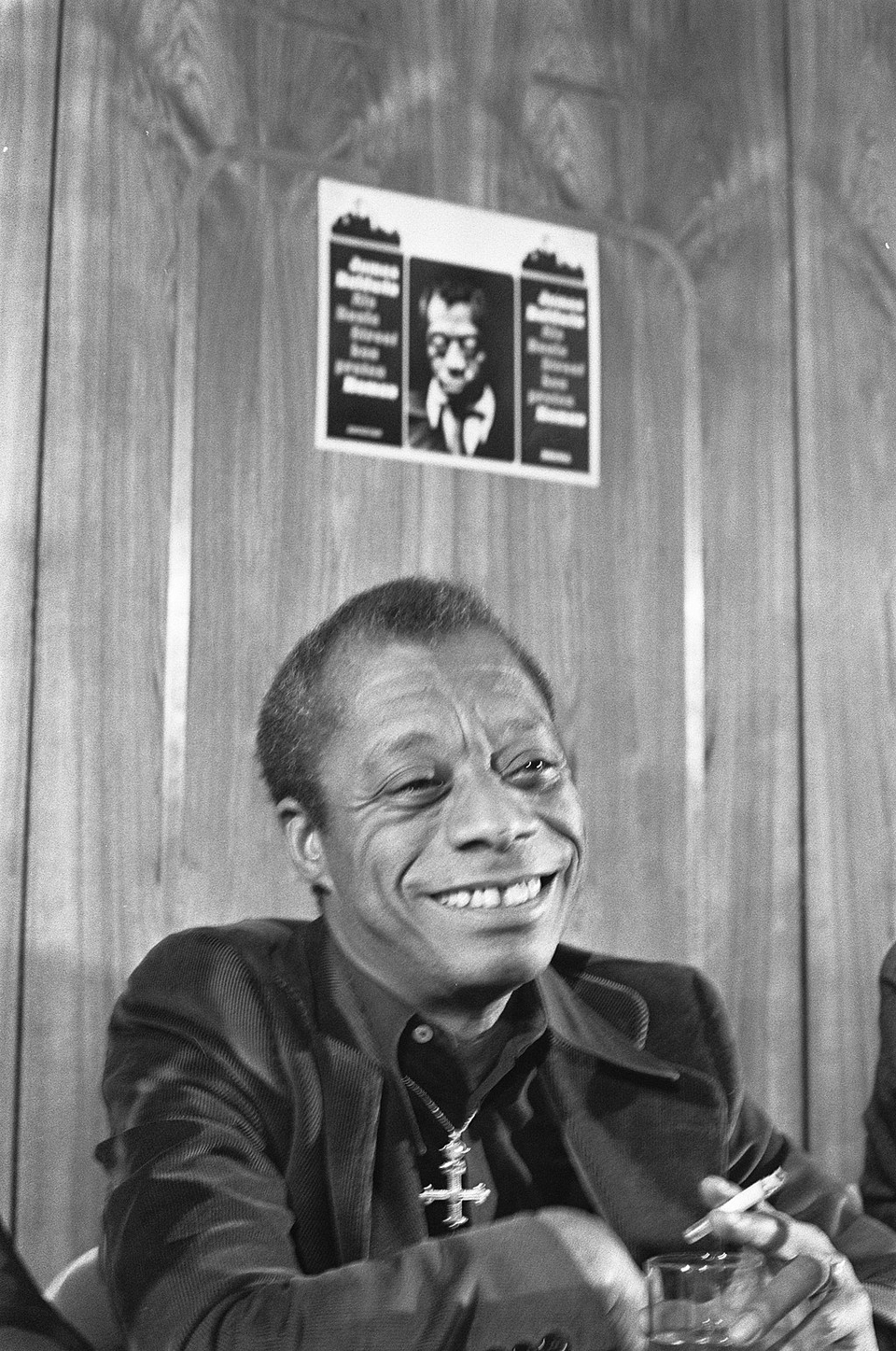

Born on 2nd August 1924 in Harlem Hospital, New York, James Arthur Baldwin was an essayist, playwright, activist, and novelist at a time when the truths he had to name could so easily have cost him his life, and often nearly did.

Writing at the height of the civil rights movement, Baldwin lost close friends regularly to racist violence which in part led him to find a home in France. Of the losses he endured, the most significant was undoubtedly the loss that came with the murder of the Reverend Dr Martin Luther King Jr which led to a temporary eclipse of the sun in Baldwin’s life.

I suspect that Baldwin saw in King something of a father figure, or at least one who held out a hope for a Christianity that had not completely lost its way. Perhaps in King, Baldwin saw something of what Garrett describes as Baldwin’s own gift:

To be a witness is to tell the truth about the lives we’re living, the lies we’re living. It is to stand up and say what is wrong – and what is right. (p.106)

Garrett also reminds us that Baldwin was such a radical figure that despite his friendship with King he was considered too radical to be on the dais with King and other civil rights leaders when King made his ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech. (p.139).

The eldest of nine children, the grandson of an enslaved African and an openly gay man at a time when homosexuality was still illegal, Baldwin’s identity meant that he perceived things in himself and in society that many chose to ignore or wilfully collude in, and his choice to speak about these things was a testament to his courage. For Baldwin, both Black and White people needed to name truths about their histories in order to be truly free – but also the Church had to name its manifold failings and complicity in the sins of racism and homophobia, a Church which Baldwin knew intimately as a young preacher.

Though he left the Church, Garrett’s book reminds us of the ways in which the grammar of Christian life was so deeply rooted in Baldwin as a person, a grammar which resurfaces in almost every piece of his writing. Baldwin’s great gift was the way in which he simply told the world the truth about itself living out a vocation which was simply ‘to bear witness to the truth’ (p.63) and in doing so he held up a mirror that had written on it the reminder: ‘we can be better than we are’.

In a sense I think this is Baldwin’s way of embodying the Gospel he came to know as a young preacher – Jesus holds out for us in his life, death and resurrection – a choice…to turn, to life, to truth, to love, and to be saved. But it is, at the end of the day, a choice.

Perhaps most prescient for us as a diocese is the way Garrett reminds us of Baldwin’s challenge to institutional Christianity – as a Black gay man Baldwin knew exclusion in more than just one sense. And thus he reminds us that it is never too late to become the people God has called us to be. As Garrett so beautifully puts it:

We are all better than our worst acts.

We are always in a state of becoming.

We are each looking for the place we belong and the people who will love and understand us.

And we need the help of writers, artists, priests, and prophets to find those things. (p. 25

In his recently published The Gospel According to James Baldwin: What America’s Great Prophet Can Teach Us About Life, Love and Identity, Greg Garrett reminds us of the deep theological and spiritual riches to be found in James Baldwin’s work, aspects which in the life of Baldwin I feel have been too long overlooked.

I don’t think that Baldwin ever visited Wales, but it is worth us thinking – if he stood in the pulpit of St Deiniol’s today- as he did in Uppsala when invited to address the World Council of Churches in 1968 - what might he have to tell us about our life together that we do not want to hear, or are yet to acknowledge? As Garrett says:

If all of us who love and admire Baldwin take [his] calling seriously – to be honest about ourselves and about the world, to call out what is wrong, to stand up for what is right – then we have no choice but to speak, preach, teach, write, march, vote, transport, feed, house, nurture, boycott, and lend our fee and heads and hands to the quest for justice. (p.141)

The Reverend Canon Jarel Robinson-Brown is Assistant Curate in the Diocese of London, Visiting Scholar at Sarum College, Salisbury, Co-Chair of OneBodyOneFaith and Canon Preacher of St Deiniol’s Cathedral, Bangor.